Part 3: Is Canada Different?

As you can see in the chart above, debt levels can change over time. Prices and incomes rise or fall, and debts are paid off over time (or defaulted). It’s the starting point that matters, and Canada’s markets are now climbing to historically high home prices and dangerous levels of debt.

However, it may not be bad debt.

In the years leading up to the financial crisis, lending standards in the United States were famously lax. From 2001 to 2006, subprime loans (risky loans with a high chance of default) went from 7.5% of the mortgage market to 23.5%. The latest data from The Bank of Canada claims that subprime mortgages are no more than 5% of Canada’s market.

Canada has also made six major adjustments over the past ten years that were designed to prevent lending standards from deteriorating; potential homebuyers are now required to pass a “stress test” ensuring that they can continue making payments if interest rates go up, are required to make a down payment of 20% or 35% if they want to avoid paying mortgage insurance, and face other various restrictions on borrowing. The list is extensive, but the short version is that all of these standards are much more stringent than the United States, with the biggest major difference being that Canadian mortgages must be repaid in full even after a foreclosure, while American mortgage borrowers can “hand over the keys and walk away” from the loan.

It still might not be enough to prevent a bubble.

One effect of the new standards, and a reason to doubt the real number of subprime loans, is that more borrowers are using Canada’s “shadow banking” system that is not regulated or backed by the Canadian government. This is made up of companies called “alternative lenders”, which are groups of investors that offer high interest mortgage loans and often hide the true quality of their lending. This group of lenders has jumped from 6.6% of the mortgage market in 2007 to 12.5% in 2015; today’s number is somewhat unknown, with different sources claiming that it’s anywhere from 2% to 10%—but nobody really knows.

Another huge source of concern for Canada’s real estate market is foreign buyers, especially Chinese buyers, who simply lie about their finances to secure funding for speculative real estate bets—in a direct response to these concerns, Vancouver and Toronto both added a 15% tax on foreign buyers, but it may be too late.

On top of this slow-moving decline in lending standards, what we’re seeing now is a market that looks like it’s starting to turn: the hottest markets, Vancouver and Toronto, have started to cool down a little; in Alberta, a province that closely follows the oil industry’s market cycle, foreclosures have gone up by 25% over the past two years; in aggregate, the most recent data shows that home sales have dropped in 70% of the local markets, and vacancy rates are at 3.7% nationally (not too high yet, but rising), their highest level since 1998.

Goldman Sachs—citing a potentially overbuilt market and excessive household debt—is cautiously giving Canada’s real estate market a 30% chance of collapsing within the next two years, its highest estimate since 2010. Even the most perpetually optimistic market forecasters concede that rising interest rates will probably be the catalyst that tanks the market.

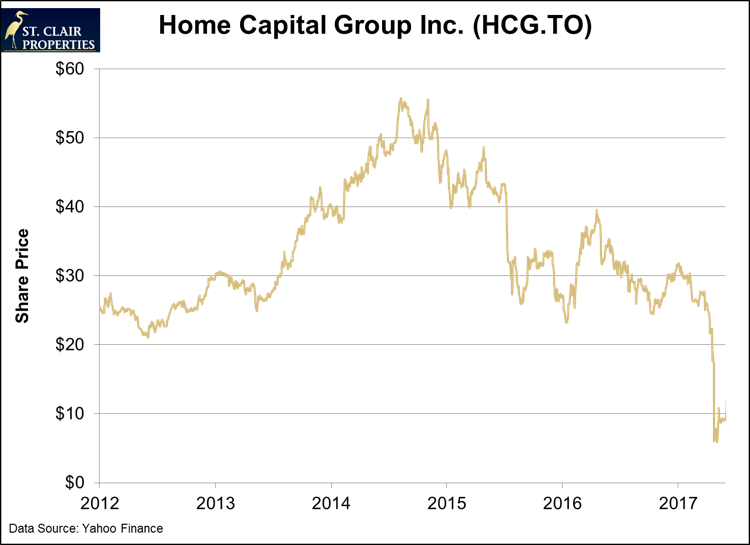

One Canadian subprime lender, considered a warning of what’s coming, set a record last April for the fastest stock collapse in history. Home Capital Group, Canada’s largest non-bank mortgage lender, fell 60%, in one day, after disclosing that it needed a C$2 billion (US$1.5 billion) loan, with an effective interest rate (including charges and fees) of roughly 22%, to save it from bankruptcy.

This came after two years of warnings about the company’s dangerous lending practices—many of which were almost identical to what the United States was doing right before 2008.

The stock has sharply rebounded within the past month, when the company was bailed out again, but we’ll get to that part later. This is how it looked at the end of May.

If you ask the Canadians?

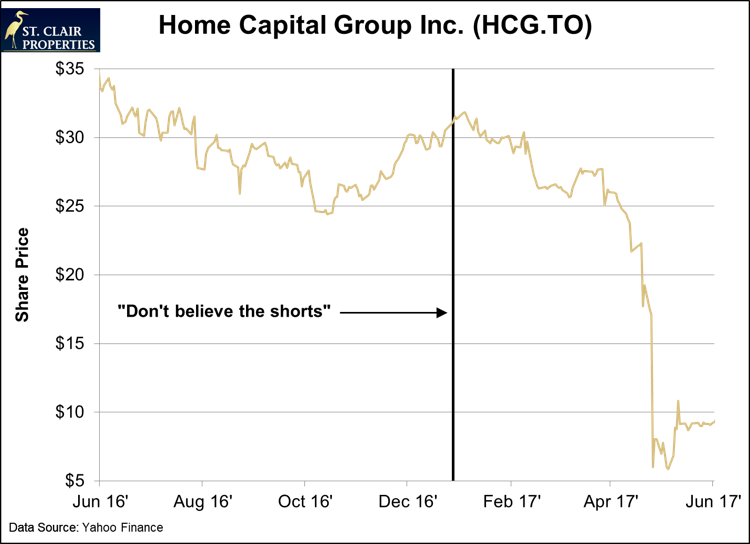

Back in December of 2016, it was “Don’t believe the shorts betting against Canada’s Home Capital”—basically, what they were saying was that Home Capital Group has a strong history of operating performance and that “this time is different.” At the time, it was the most shorted company in the Canadian market.

Take closer look at that chart.

The shorts were right.

And shortly after Home Capital Group’s collapse, Moody’s rating service, citing increasing levels of leverage in the Canadian financial system, downgraded its rating for 6 of Canada’s largest lenders. The credit downgrade was “unrelated to Home Capital Group,” and the country’s economy is still doing fine, but it came with concern that there is future trouble on the horizon.