On April 4th, the Oregon House of Representatives passed House Bill 2004 in a 31 to 27 vote along party lines, with most Democrats voting yes and most Republicans voting no. The bill, a controversial attempt to change the relationship between landlords and tenants, is currently under review by the State Senate. It has two main parts: The first part limits a landlord’s ability to evict tenants without cause. The second part removes Oregon’s statewide ban on rent controls.

Both parts have far-reaching effects, but we’re more interested in the second part. Allowing rent controls (the bill only allows municipalities to enact rent controls; it doesn’t create any rent controls) is a major shift for a state that banned them in the 1980s.

How did we get here?

The modern form of rent controls started with World War II, when a shortage of homebuilding materials, caused by the war effort, led to a housing shortage. The housing shortage put an immense amount of upward pressure on rental rates, and the Federal government, as part of its economy-wide program to control prices, stepped in to keep the rent from escalating out of control.

Using temporary price and rent controls to help win World War II is hard to criticize, but the next nation-wide set of price and rent controls had a less admirable foundation. Called the “Nixon Shock,” it came when President Nixon signed Executive Order 11615 in 1971. The order, which took the US off the gold standard, created a set of economic programs that included price and rent controls. The price controls were enormously popular and are credited as part of what helped Nixon get re-elected (the program conveniently ended shortly after his re-election).

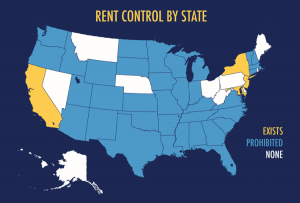

Since 1973, after another set of Nixon price-controls, rent control has been a state issue. There are currently only four states, plus DC, that have rent control, while 35 states have laws preventing rent controls.

Source: National Association for Multifamily Law

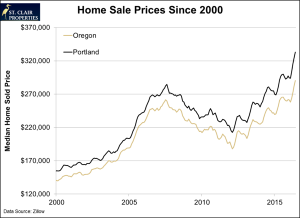

For Oregon, one of the 35 states that don’t allow any rent controls, the new rent control bill is an answer to a statewide housing shortage, most severe in Portland and Salem, which has built up over the past ten years. The state’s economist estimates that Oregon has a shortage of 111,000 housing units, six times what was built in 2016, and Oregon has the lowest housing inventories since 2005.

This shortage, like the national housing shortage of the 1940s, is already affecting Oregon’s home prices—Portland is now leading the nation with housing costs that rose by 11.1% last year.

Fast-moving home prices are not entirely a bad thing. It’s the mark of a city and a state that is attracting more people and more jobs, and those are both demographic changes to be proud of.

The problems come when the housing supply doesn’t keep up with the housing demand and when wages don’t keep up with housing costs. Compare Portland’s 11.1% jump in housing costs to its 3% increase in wages, and it’s easy to see a city that’s becoming unaffordable for its essential service workers. That’s why the Oregon state government is desperately evaluating the options.

Is Rent Control the Right Solution?

Economists disagree on many social programs, but they are virtually unanimous on this one—rent control doesn’t work.

A politically diverse group of economists, from the free market icon Milton Friedman to the left-leaning Paul Krugman, all oppose rent controls. A 1992 survey of experienced economists found that 93% believe ”a ceiling on rents reduces the quality and quantity of housing.” For such a polarizing topic, that’s almost universal agreement.

So what’s wrong with rent control? We have two ways to approach this question. The first way examines economic theory, and the second explores the effects that we can see in the real world.

According to economic theory, any kind of price ceiling (a fixed maximum price) will generate a permanent shortage when the price is set below the market rate. When the price is too low, suppliers will not have an incentive to offer more; they will take their money to other markets that offer higher returns.

For real estate, this means that a landlord won’t feel the need to improve their housing properties (they’ll get the same rent either way), and developers will avoid building housing units that are subject to rent controls (they might, for example, focus on more profitable commercial developments instead).

These effects hurt struggling families—the same people that rent controls are trying to help. Rent-controlled housing is more likely to be low-quality. At the same time, competition among potential tenants drives up the rent for the remaining housing units that aren’t subject to rent controls, and the most risky renters are still excluded from rent-controlled housing units. This is not what rent controls are intended to achieve.

The real world data backs up the theory.

For one, there’s a big difference in quality—in the US, 29% of rent-controlled housing needs major repairs, while only 8% of non-controlled units have the same problems.

In more specific US markets, we have the famously rent-controlled (and famously expensive!) cities of New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco.

New York is one of the cities that continued, in some form, the rent control policies from World War II, and currently has about half of its housing units under some kind of rent control. The result was that New York saw a housing boom, but only in housing that wasn’t subject to rent controls. Before rent stabilization was added in 1969, New York built about 35,000 housing units each year. By the 1980s, this dropped to 10,000. Part of the reason why is because developers feared—even when the city promised not to add rent controls for new units—that some form of rent controls would eventually be added.

On the other side of the country, Los Angeles and San Francisco, both part of a long list of rent-controlled California cities, are continually competing for who has the most “screwed up” housing market.

An astronomical 85% of Los Angeles housing is protected by rent stabilization, and the city is estimated to need another 35,000 housing units to alleviate its current housing crisis. San Francisco falls short by about 15,000 housing units. These shortages, even with rent control protections, have driven rents up to the point where residents of LA put 48% of their income into rent, and San Franciscans spend 44% of their income on rent.

Low-income tenants are still getting pushed out, too. In LA, the wait list for Section 8 rental assistance was closed a few years ago when it reached 200,000 people; after dropping people who were ineligible, it now has 40,000 names. Even with added incentives for landlords to accept these tenants, the waiting time is currently 11 years, and the city struggles to convince landlords to take in these tenants. San Francisco is also notoriously difficult to move into, with numerous stories of potential tenants literally begging for a space.

Rent controls are not solving the housing problems for these cities.

What’s the Alternative?

On the most basic level, rent is the price that comes from where housing rental supply (the number of housing units available for rent) meets housing rental demand (the number of people available to rent). When the demand goes up faster than the supply, the price (the rent) goes up. This is what’s happening in California—for every 1000 new residents in the city, Los Angeles only builds 187 new housing units, and San Francisco builds 193 new housing units. It’s a deficit that has been growing for decades.

High rents are a challenge for tenants, but they’re actually a symptom of a different problem; one that won’t be fixed by fixing the price.

Building more housing units is the only real long-term solution for a growing city. Finding ways to increase wages could be a temporary fix, but until the housing supply catches up to the housing demand, rents will continue to outstrip wage growth.

It’s still a difficult problem, because one thing that many rent controlled cities have in common is that they are usually hemmed-in by mountains or coastline, leaving no opportunity for expanding outward. This means that new construction must build upward with high-density apartment complexes. That requires rezoning and adding incentives for building new housing units, something that is often loudly resisted by voters.

The voters may not like it, but rezoning for high density housing will help them more than rent control. This is true even for cities that have the option of sprawling outward.

High density buildings make living cheaper. These buildings can be made cheaper per unit—they can be built to use existing infrastructure, eliminating the need to add more roads and pipes, and economies of scale allow developers to secure cheaper building materials, lowering the cost of building’s initial construction. They also save money for the people who eventually move in—studies have shown that housing and transportation costs for “compact cities” are 25% to 50% cheaper than sprawling cities.

High density buildings are also more environmentally friendly. Rejuvenating the land inside the city preserves the edges for forests and fields, and energy use drops by at least 15% in a compact city.

The benefits are clear. Cities that are struggling to find room for more people should be building more high density housing. That’s the right alternative to rent control.

Conclusion

The problem with Oregon House Bill 2004 is that it’s trying to fix the wrong problem. As noted by several of the state’s House Representatives, this bill won’t build any new housing units. There are other bills under consideration that are intended to encourage new housing projects, but they won’t have much of an effect when Oregon cities start wiping out the local real estate returns.

Removing the ban on rent controls is a dangerous approach to the state’s housing crisis. If the State Senate doesn’t see what is happening in California, it will be a rough road ahead for both Oregon landlords and their tenants.